- Log in to:

- Community

- DigitalOcean

- Sign up for:

- Community

- DigitalOcean

Introduction

Nginx is one of the most widely used web servers and reverse proxies in the world. Known for its performance and scalability, it can handle thousands of concurrent connections efficiently while serving as a web server, load balancer, or gateway for complex application architectures.

This guide explains how Nginx decides which configuration blocks handle incoming requests. These blocks, called server and location blocks, form the core of how Nginx maps domains, IP addresses, and request URIs to specific content or backend applications. By understanding how Nginx evaluates these blocks, you can write configurations that behave predictably, prevent routing conflicts, and simplify debugging.

By the end of this guide, you will understand how Nginx interprets and prioritizes server and location blocks, the sequence of evaluations that occur when a request arrives, and the rules, modifiers, and exceptions that determine which configuration is used. This knowledge will help you design clean and maintainable configurations and troubleshoot routing issues with confidence.

Key Takeaways:

listenDirective Priority: Nginx first filters server blocks based on thelistendirective. It checks the IP address and port specificity before evaluating any domain names. A block listening on a specific IP (e.g.,192.168.1.10:80) takes precedence over a block listening on0.0.0.0:80.server_nameEvaluation Order: When multiple server blocks define the same IP and port, Nginx compares theHostheader againstserver_namedirectives in a strict order: exact match, leading wildcard (e.g.,*.example.com), trailing wildcard (e.g.,www.example.*), and finally, regular expressions.- Default Server Fallback: If the

Hostheader does not match any definedserver_name, Nginx routes the request to the default server for that IP/port combination. This is either the first block defined in the configuration or the block explicitly marked with thedefault_serverparameter. - Location Modifier Hierarchy: Location blocks use specific modifiers to determine matching behavior. The

=modifier checks for an exact match,~indicates a case-sensitive regular expression,~*indicates a case-insensitive regular expression, and^~performs a prefix match that disables subsequent regex checks. - Regex Overrides Prefix (Usually): By default, Nginx prioritizes regular expression matches over standard prefix matches, even if the prefix match is longer. It evaluates all prefix locations first to find the longest one, but will switch to a regex match if one is found subsequently.

- The

^~Circuit Breaker: The^~modifier is a powerful tool for performance and logic control. If the longest matching prefix location uses^~, Nginx immediately stops searching and ignores all regular expression locations, using that prefix block to serve the request. - Exact Match (

=) Efficiency: Using the=modifier forces an exact string match against the URI. If found, Nginx terminates the search immediately. This is the most efficient method for handling specific, frequently accessed URIs. - Internal Redirects Restart Search: Directives such as

index,try_files,rewrite, anderror_pagecan trigger an internal redirect. This causes Nginx to restart the location selection algorithm from the beginning with the new URI, potentially matching a different location block than the original request.

Why Server and Location Selection Matters

Every request that reaches an Nginx server follows a precise evaluation process. Understanding how Nginx selects the appropriate server and location block is essential for maintaining predictable behavior and avoiding routing errors. When multiple blocks overlap or contain similar patterns, Nginx applies a strict order of evaluation to decide which one will handle the request. Without a clear understanding of this process, even small configuration changes can lead to unexpected results.

A common example is when two location blocks match a similar URI pattern. If one uses a regular expression while another uses a prefix, the order in which they appear and the modifiers they use can completely change the outcome. Likewise, two server blocks listening on the same port but configured with different domain names may cause requests to be routed incorrectly if the server_name directive is not defined properly. These subtle differences often create confusion for administrators who are unsure which block Nginx will choose at runtime.

Knowing how the selection process works removes that uncertainty. It allows you to create configuration files that are both efficient and readable. You can confidently predict how Nginx will interpret each directive, prioritize matches, and handle exceptions triggered by directives like rewrite or try_files.

The complete selection process can be divided into three major phases:

- Server block selection: Nginx determines which server block will handle the request by comparing the client’s IP address, port, and host header against all defined

listenandserver_namedirectives. - Location block selection: Within the chosen server, Nginx identifies the most specific location block by testing the request URI against all available matches.

- Internal redirects: If an internal redirect occurs because of directives such as

index,try_files,rewrite, orerror_page, Nginx restarts the location search within the same server context to find the final handler.

Together, these phases ensure that each request is routed to the correct destination in a consistent and predictable way. A solid understanding of this process is the foundation for building reliable and maintainable Nginx configurations.

Understanding Nginx Configuration Blocks

Nginx organizes its configuration into a hierarchy of blocks that determine how requests are processed. Each block defines specific behavior for a context, such as which port to listen on, how to handle certain file paths, or when to pass traffic to another service. Understanding how these blocks work together is the first step toward interpreting Nginx’s request handling logic.

Server Blocks Overview

A server block defines a virtual server that handles requests based on specific network parameters. Each block typically includes directives that specify the IP address, port, and domain name combinations that it will respond to. Server blocks are often used to host multiple domains or applications on the same Nginx instance.

A basic configuration might look like this:

server {

listen 80;

server_name example.com;

root /var/www/example;

}

In this example, Nginx will respond to HTTP requests sent to port 80 for the domain example.com. You can define multiple server blocks within a single configuration file, allowing Nginx to serve different content depending on the Host header and the request’s destination address.

Location Blocks Overview

A location block lives inside a server block and controls how requests for specific URIs are processed. The URI is the portion of the request that follows the domain name or IP address. Location blocks can define how static files are served, when to apply caching rules, or when to forward traffic to upstream servers.

For example:

location /images/ {

root /var/www/static;

}

This block handles requests for any URI beginning with /images/. Location blocks are flexible and can match URIs using exact strings, prefixes, or regular expressions. The matching method you choose determines how Nginx prioritizes and processes requests.

Nested Locations and Inheritance

Nginx allows configuration blocks to be nested. This hierarchical structure makes it possible to define general rules at a higher level and then override them within more specific contexts. For instance, a location block can inherit directives from its parent server block but also redefine them when necessary.

When a request is processed, Nginx applies directives from the main context, the server block, and finally the matching location block. Directives that appear deeper in the hierarchy take precedence unless explicitly designed to merge or inherit. This layered approach helps maintain consistent behavior while allowing precise control where it is needed.

Certain directives can trigger what is called an internal redirect, which causes Nginx to restart the location search process. When this happens, the current request may jump to another location block that better fits the rewritten or redirected URI. Internal redirects can occur with directives such as:

indextry_filesrewriteerror_page

Understanding when these jumps occur is critical because they can change which location block ultimately handles a request. These internal evaluations will be discussed in detail later when we explore Nginx’s location selection algorithm.

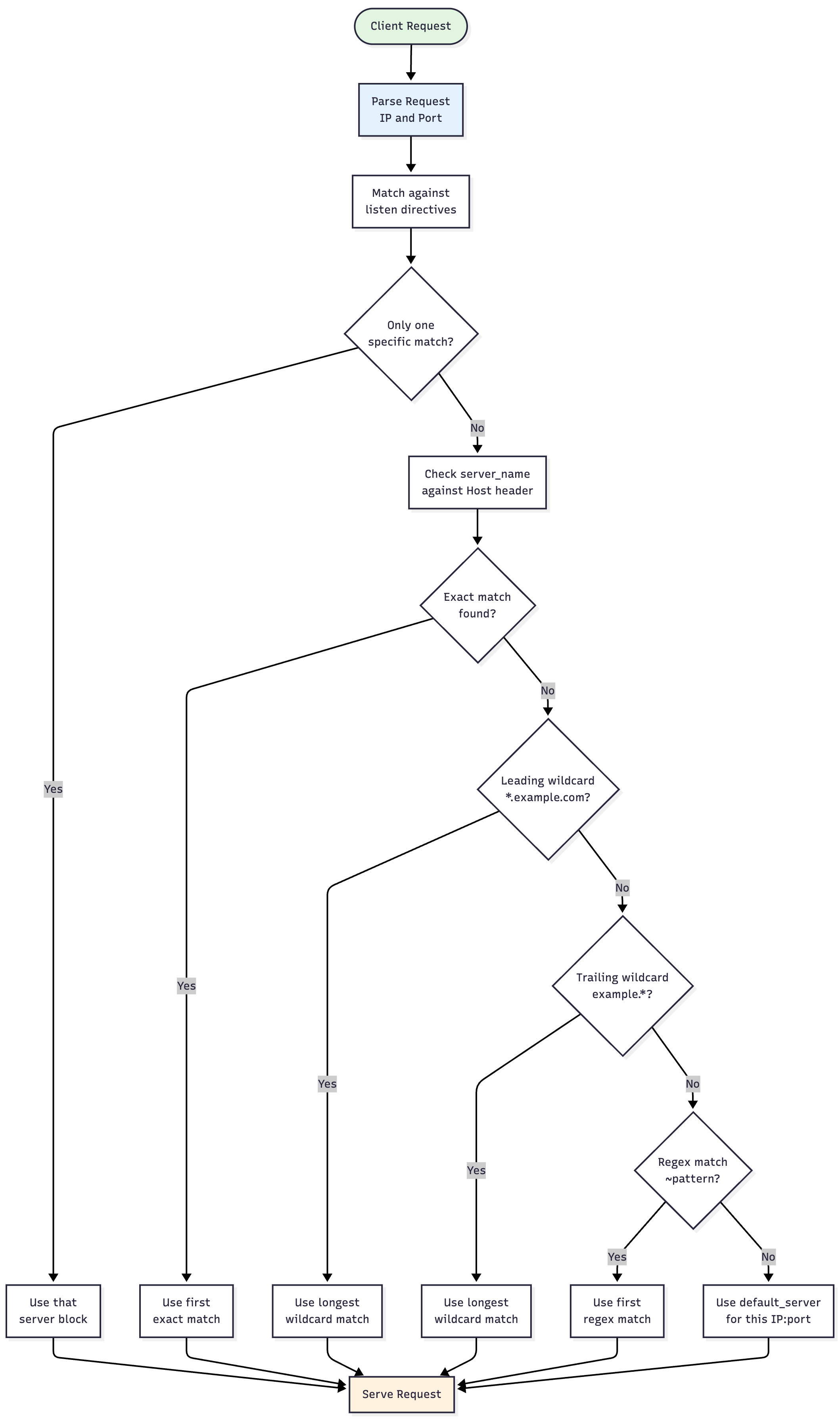

How Nginx Selects the Server Block

Before Nginx can process a request, it must decide which server block will handle it. Each request is compared against all available server blocks in the configuration, and Nginx uses a defined series of checks to find the most specific match. This selection process is based on the values of the request’s IP address, port, and Host header, which Nginx compares against each block’s listen and server_name directives.

Matching the listen Directive

The first step is to match the request’s IP address and port with the values defined in each listen directive. The listen directive tells Nginx which IP address and port combination a server block will respond to. For example:

server {

listen 80;

server_name example.com;

}

A request sent to port 80 on the host will match this block as a candidate.

If multiple server blocks have compatible listen directives, Nginx continues to the next evaluation step, but first it normalizes all listen values to complete IP-and-port pairs. This normalization helps ensure a consistent comparison.

Nginx applies the following logic when interpreting listen directives:

- A block without a

listendirective is treated as0.0.0.0:80(or0.0.0.0:8080if Nginx runs as a non-root user). - An IP address without a port, such as

listen 111.111.111.111;, is interpreted as111.111.111.111:80. - A port without an IP address, such as

listen 8080;, is treated as0.0.0.0:8080. - The path to a Unix socket can also be used for communication between services.

After normalization, Nginx collects all server blocks that match the incoming IP and port, applying the following specificity rules:

- Blocks with a specific IP address take priority over those that use a wildcard (

0.0.0.0). - If multiple blocks are equally specific, Nginx temporarily selects the first one defined in the configuration until the

server_namedirective resolves the tie.

Default Server Handling

Each IP-and-port combination must have one default server, which handles requests that do not match any defined server_name. If no default_server is declared, Nginx uses the first block defined for that combination as the default. You can explicitly define one with:

server {

listen 80 default_server;

server_name _;

}

This ensures that unmatched requests are handled predictably.

It is important to understand that Nginx only evaluates the server_name directive when there is more than one server block with an equally specific listen definition. For example:

server {

listen 192.168.1.10;

}

server {

listen 80;

server_name example.com;

}

If a request for example.com is sent to port 80 on 192.168.1.10, Nginx will always select the first block, because it matches the IP address exactly. The server_name directive is not considered here.

Matching the server_name Directive

If multiple server blocks share the same IP and port, Nginx compares the request’s Host header to each block’s server_name directive to find the most appropriate match. The server_name directive can contain exact names, wildcards, or regular expressions.

Nginx evaluates server_name directives in this order:

- Exact match: The

server_namematches theHostheader exactly. - Leading wildcard: A pattern such as

*.example.commatcheswww.example.comormail.example.com. If multiple leading wildcards match, the longest one is chosen. - Trailing wildcard: A pattern such as

mail.*matchesmail.example.comormail.org. Again, the longest match wins. - Regular expression match: A

server_namebeginning with~is treated as a regular expression, and the first matching block is used. - Default server: If no match is found, Nginx uses the default server block for the current IP and port combination.

Examples

If a server_name matches exactly, that block is selected immediately:

server {

listen 80;

server_name *.example.com;

}

server {

listen 80;

server_name host1.example.com;

}

A request for host1.example.com will be handled by the second block because it provides an exact match.

If no exact match is found, Nginx checks for leading wildcards. For example:

server {

listen 80;

server_name www.example.*;

}

server {

listen 80;

server_name *.example.org;

}

server {

listen 80;

server_name *.org;

}

A request for www.example.org will be handled by the second block because it provides the longest leading wildcard match.

Next, Nginx checks for trailing wildcards:

server {

listen 80;

server_name host1.example.com;

}

server {

listen 80;

server_name example.com;

}

server {

listen 80;

server_name www.example.*;

}

For a request to www.example.com, the third block will be used, since it provides the longest trailing wildcard match.

If no wildcard matches are found, Nginx evaluates regular expression server_name definitions in the order they appear. The first one that matches is selected. For instance:

server {

listen 80;

server_name example.com;

}

server {

listen 80;

server_name ~^(www|host1).*\.example\.com$;

}

server {

listen 80;

server_name ~^(subdomain|set|www|host1).*\.example\.com$;

}

A request for www.example.com will match the second block, since it is the first regular expression that fits.

If no matches are found, Nginx defaults to the first block for that IP and port, or whichever block explicitly uses default_server.

Version Differences

The server selection process works the same in NGINX Open Source and NGINX Plus. The core algorithm, evaluation order, and matching behavior do not differ. However, NGINX Plus includes diagnostic tools, such as the API and dashboard modules, that make it easier to inspect active configurations and understand which server block is serving a request. Both versions adhere to the same selection logic described in the official documentation.

Here’s a simple flowchart that illustrates this entire process:

Understanding Location Block Types

After Nginx selects the appropriate server block, it must determine which location block within that server should handle the request. The location block defines how Nginx processes specific URIs (the part of the URL that comes after the domain name or IP address). Understanding the different types of location matches is essential for writing predictable and maintainable configurations.

Location Block Syntax

A location block is defined using the location directive inside a server block. The general form is:

location [modifier] match_pattern {

# configuration directives

}

modifier: An optional symbol that changes how Nginx interprets thematch_pattern.match_pattern: The string, prefix, or regular expression used to test against the request URI.

Each modifier has a specific meaning that affects how Nginx performs the match and how the algorithm prioritizes one location block over another.

Prefix Match (default)

If no modifier is specified, Nginx performs a prefix match. This means the location block matches all URIs that start with the specified prefix. Prefix matches are case-sensitive and are the most common type used in Nginx configurations.

location /images/ {

root /var/www/static;

}

In this example, any request beginning with /images/ (such as /images/logo.png or /images/icons/set1/) will be processed by this block.

Prefix matches are efficient and fast to evaluate, making them ideal for static content and common directory-based routing.

Exact Match (=)

If a location is defined with the = modifier, Nginx treats it as an exact match. The block is used only if the request URI exactly equals the specified path.

location = /index.html {

root /var/www/site;

}

A request for /index.html will match this block exactly, while /index.html?ref=home or /index.html/ will not. Exact matches have the highest priority and immediately terminate the search process when found.

Administrators often use exact matches to serve small, fixed files such as the home page or favicon, where the path does not vary.

Case-Sensitive Regular Expression (~)

A location defined with the ~ modifier is evaluated as a case-sensitive regular expression. Nginx tests the request URI against the regex pattern and uses the first location that matches.

location ~ \.(jpe?g|png|gif|ico)$ {

root /var/www/images;

}

This example handles image requests ending in .jpg, .jpeg, .png, .gif, or .ico. Regular expression locations are powerful but should be used carefully, as they are slower than prefix matches and can introduce complexity in debugging.

Case-Insensitive Regular Expression (~*)

A location defined with the ~* modifier performs a case-insensitive regular expression match.

location ~* \.(jpe?g|png|gif|ico)$ {

root /var/www/images;

}

This version matches both /tortoise.jpg and /FLOWER.PNG, making it suitable when the case of incoming requests cannot be guaranteed (for example, with user-generated or legacy URLs).

The ^~ Modifier

The ^~ modifier is used to indicate that if a prefix match using this block is the longest match so far, Nginx should skip all subsequent regular expression checks and use this block directly.

location ^~ /static/ {

root /var/www/assets;

}

In this case, if the request URI begins with /static/, Nginx will immediately use this block and will not check any regex-based locations. This is useful when you want prefix matches to take precedence over more flexible but slower regex evaluations.

Summary Table of All Location Modifiers:

| Modifier | Match Type | Case Sensitivity | Evaluation Order | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (none) | Prefix | Case-sensitive | Longest prefix | location /app/ {} |

Matches all URIs starting with /app/. |

= |

Exact | Case-sensitive | Highest priority | location = /index.html {} |

Matches only /index.html. |

^~ |

Prefix | Case-sensitive | Before regex phase | location ^~ /static/ {} |

Longest prefix match; skips regex evaluation. |

~ |

Regex | Case-sensitive | Sequential (first match) | location ~ \.php$ {} |

Matches using regex pattern. |

~* |

Regex | Case-insensitive | Sequential (first match) | location ~* \.(jpg|png)$ {} |

Matches regex ignoring case. |

Examples of Each Location Type

Example 1: Prefix match

location /downloads/ {

root /var/www/public;

}

This block matches any request whose URI begins with /downloads/. For instance, /downloads/file.zip, /downloads/manual.pdf, or /downloads/archive/data.tar.gz will all be handled here.

Example 2: Exact match

location = /robots.txt {

root /var/www/site;

}

This block will only process requests that exactly match /robots.txt. It will not match /robots.txt/, /robots.txt?v=1, or any subpath.

Example 3: Regex match

location ~ \.php$ {

fastcgi_pass unix:/run/php/php7.4-fpm.sock;

}

This configuration matches all URIs ending in .php, such as /index.php, /user/profile.php, or /admin/login.php. Because the ~ modifier specifies a case-sensitive regular expression, /INDEX.PHP would not match this rule.

Example 4: Case-insensitive regex

location ~* \.(jpg|jpeg|png)$ {

root /var/www/images;

}

This block matches image file requests regardless of letter case, such as /photo.jpg, /photo.JPG, or /gallery/PICTURE.PNG. The ~* modifier makes the pattern case-insensitive, ensuring consistent handling of requests from clients that may vary in case sensitivity.

Example 5: The ^~ modifier

location ^~ /api/ {

proxy_pass http://backend_server;

}

This rule tells Nginx to immediately select this block if the URI begins with /api/, without checking any subsequent regex-based locations. For example, requests like /api/v1/users, /api/status, or /api/data.json will all be handled here.

Different location modifiers allow you to fine-tune how Nginx matches request URIs. Prefix and exact matches are generally faster and easier to reason about, while regex-based matches provide flexibility for complex patterns. The next section will explain how Nginx uses these modifiers to determine which location block is selected when multiple matches are possible.

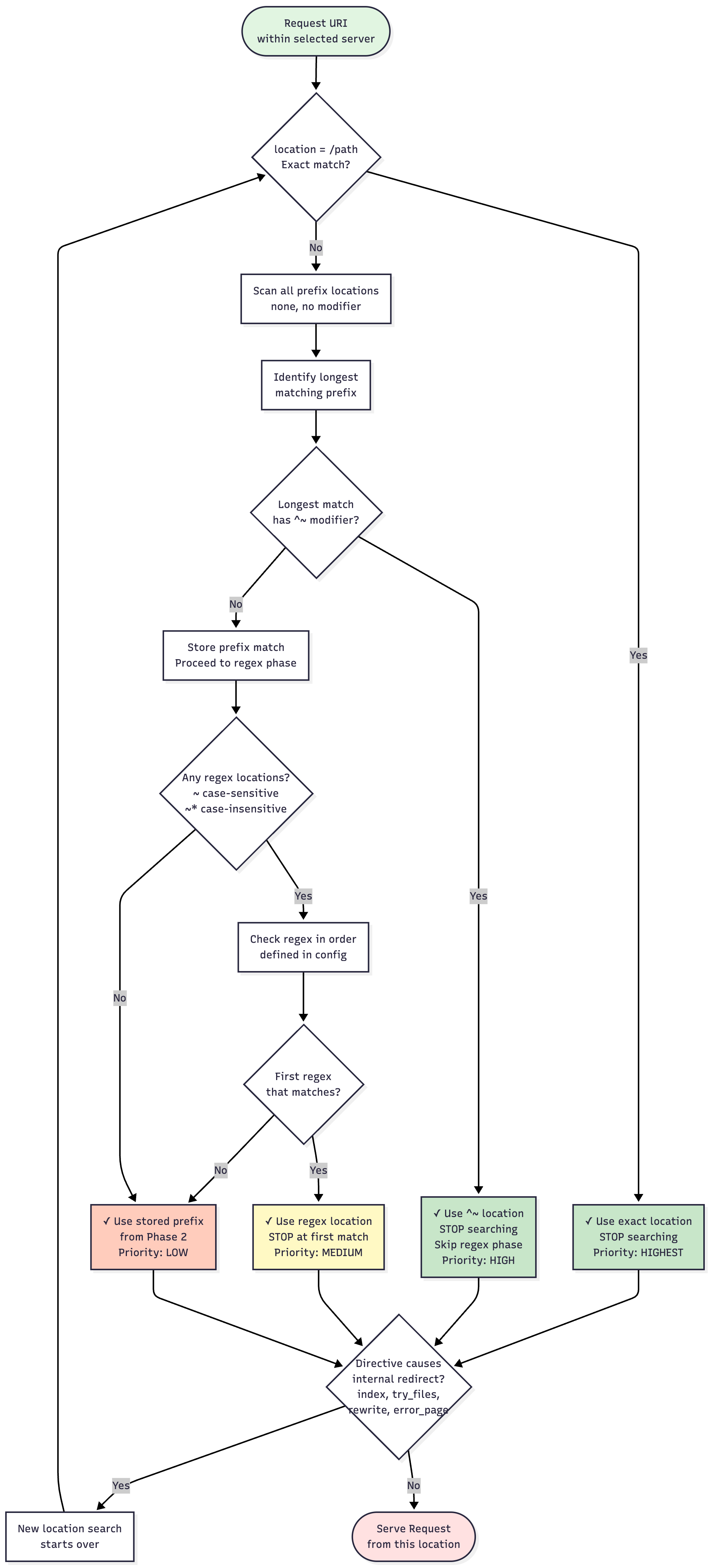

How Nginx Selects the Location Block

After selecting the correct server block, Nginx determines which location block within that server will process the request. The location block defines how the server handles specific URIs, whether that means serving static files, proxying requests, or rewriting paths.

The selection algorithm follows a strict, multi-step order designed to prioritize precision while maintaining efficiency. Each stage filters possible matches until Nginx identifies a single, definitive location for the incoming URI.

Prefix Match Phase (Exact -> Longest Prefix)

The first stage of Nginx’s location selection focuses on prefix-based matches. Prefix locations are the simplest and fastest type because Nginx compares the beginning of the URI as a plain string. The process starts with exact matches, then moves on to general prefix comparisons.

An exact match is defined using the = modifier. When a URI exactly equals the specified string, Nginx immediately stops searching and serves that block. For example:

location = /index.html {

root /var/www/html;

}

This block only handles /index.html. Requests like /index.html?v=2 or /index.html/ will not match. Because exact matches are evaluated first, they take precedence over all other locations.

If no exact match exists, Nginx compares the URI against all other prefix locations (those without modifiers). It identifies every location that matches the start of the URI and stores the longest one as the candidate prefix.

location / {

root /var/www/base;

}

location /images/ {

root /var/www/media;

}

location /images/icons/ {

root /var/www/icons;

}

For a request to /images/icons/logo.png, Nginx finds that all three prefixes match, but /images/icons/ is the longest and therefore wins. The order in which these locations are defined in the configuration does not matter; only the length of the matching prefix determines priority.

When writing prefix matches, be mindful of common pitfalls:

- Trailing slashes matter. Without a trailing slash (

/appvs/app/), Nginx may also match/applicationor/app123. - Prefix comparisons are case-sensitive.

/Images/and/images/are treated differently. - The root

/matches all URIs but serves as a fallback for unmatched requests.

Prefix matches are efficient because they require no pattern parsing. They are ideal for static content, directories, or well-defined URI paths.

The ^~ Shortcut Rule

The ^~ modifier changes how Nginx handles prefix matches by instructing it to skip all subsequent regular expression evaluations if the prefix is matched. This makes ^~ useful when you want specific directories or routes to take precedence over regex rules.

location ^~ /static/ {

root /var/www/assets;

}

If the request URI begins with /static/, Nginx selects this block and does not evaluate any regex locations defined later. This rule is particularly helpful for serving static files, such as images, CSS, or JavaScript, that should bypass slower regex-based checks.

When to use ^~:

- To guarantee that certain directories are handled by static-serving blocks.

- To improve performance in high-traffic paths.

- To prevent complex regex rules from intercepting requests intended for static routes.

^~ applies only to prefix matches. Regex and exact-match blocks ignore this modifier.

Regex Match Phase

If no ^~ prefix applies, Nginx evaluates regex locations next. These are defined using ~ (case-sensitive) or ~* (case-insensitive) modifiers. Regular expression locations give you flexibility to match patterns that prefixes cannot cover, such as file extensions or case-insensitive variations.

location ~ \.php$ {

fastcgi_pass unix:/run/php/php7.4-fpm.sock;

}

location ~* \.(jpg|jpeg|png|gif|ico)$ {

root /var/www/images;

}

In the above example, the first block matches .php files exactly as written (case-sensitive), while the second matches image extensions regardless of case.

Nginx checks regex locations in the order they appear in the configuration file and stops at the first successful match. This order-sensitive behavior is a common source of confusion, as later regex definitions are ignored once a match is found.

Regex locations are slower to evaluate because they involve pattern matching, so they should be used sparingly and only when prefixes cannot achieve the same result. When combined with ^~, prefix matches can help minimize unnecessary regex evaluations.

Final Fallback Rules

If none of the regex locations match, Nginx falls back to the previously stored longest prefix match. This ensures every request has a clear, deterministic handler.

The complete evaluation order is as follows:

- Exact match (

=): stop immediately if found. - Longest prefix match (the candidate).

- If the candidate uses

^~, stop here. - Evaluate regex locations in configuration order.

- If no regex matches, use the stored longest prefix.

This order is fixed and consistent across all Nginx versions. By following this sequence, you can predict exactly which block will process any given request.

Internal Redirects That Trigger Re-evaluation

Once Nginx selects a location, it typically processes the request entirely within that block. However, some directives modify the URI or control flow in ways that cause Nginx to start the selection process again. These are called internal redirects, and they happen completely within Nginx. The client never sees them, but from Nginx’s perspective, they are treated as new requests with a different URI.

One of the most common triggers is the index directive. When a directory path is requested, such as /blog/, Nginx looks for default index files like index.html or index.php. If it finds one, it internally redirects to that file and restarts the location search for /blog/index.html. The browser still displays /blog/, but Nginx actually serves the index file behind the scenes.

The try_files directive also generates internal redirects. It tests several possible paths and serves the first one that exists. For example:

location / {

root /var/www/html;

try_files $uri $uri/ /index.html;

}

When a user requests /about, Nginx checks /var/www/html/about, then /var/www/html/about/, and if neither exists, it internally redirects to /index.html. The URI is re-evaluated, and any rules matching /index.html now apply. This behavior is widely used in single-page applications, where all unmatched routes point to a common entry page.

The rewrite directive is another source of internal redirects. When used with the last flag (or without a flag), it rewrites the URI and restarts the selection process.

location /old/ {

rewrite ^/old/(.*)$ /new/$1 last;

}

A request to /old/page.html is rewritten to /new/page.html, and Nginx then searches again for the appropriate location. If break were used instead of last, the rewrite would modify the URI but remain in the same location. The redirect and permanent flags, by contrast, send external redirects to the client rather than performing internal ones.

Finally, the error_page directive uses internal redirects to handle errors. If a file is missing or forbidden, Nginx can serve a custom page instead of a default error message:

error_page 404 /custom_404.html;

location /custom_404.html {

root /var/www/errors;

}

When a 404 occurs, Nginx redirects internally to /custom_404.html, re-evaluates the URI, and serves that page with a 404 status. Similar configurations can handle upstream failures such as 502 or 504 errors.

Internal redirects can also occur automatically. If a directory is requested without a trailing slash, Nginx appends the slash and reprocesses the URI. Modules such as auth_request or mirror can trigger subrequests that follow the same selection logic independently.

During an internal redirect, Nginx discards the current location context and restarts evaluation with the new URI, beginning again with the exact-match phase. To prevent infinite loops, Nginx limits internal redirects using the max_internal_redirects directive, which defaults to 10. If this limit is exceeded, Nginx returns an error instead of continuing.

Debugging internal redirects often requires enabling detailed logging:

error_log /var/log/nginx/error.log debug;

The logs show messages such as rewrite or internal redirection to "/new/path", indicating when a redirect has occurred. You can also log $request_uri (the original path) and $uri (the effective URI) to observe how Nginx transforms requests during processing.

Internal redirects provide Nginx with tremendous flexibility. They allow clean URLs, centralized error handling, and seamless rewrites, all without additional client requests. But because they restart location evaluation, they should be used thoughtfully to avoid loops or unnecessary complexity.

The following flowchart illustrates the selection of the location block:

Common Configuration Pitfalls

Even experienced Nginx users occasionally run into configuration issues that lead to unexpected routing, incorrect file serving, or rewrite loops. Most of these problems stem from misunderstandings about how Nginx interprets location blocks and the order in which it evaluates them. Recognizing these pitfalls can save significant debugging time and ensure that your configuration behaves as intended.

Regex Location Ordering Mistakes

One of the most common issues occurs when multiple regular expression locations are defined in a single server block. Nginx evaluates regex locations in the order they appear, stopping at the first match. This can lead to situations where a general pattern unintentionally overrides a more specific one.

For example:

location ~ \.php$ {

fastcgi_pass unix:/run/php/php8.2-fpm.sock;

}

location ~ /api/.*\.php$ {

fastcgi_pass unix:/run/php/api.sock;

}

At first glance, it might appear that API requests like /api/data.php would go to the second block, but they do not. The first regex \.php$ matches first, so all .php requests, including API endpoints, are handled by the general rule.

The correct approach is to place more specific regex locations before broader ones:

location ~ /api/.*\.php$ {

fastcgi_pass unix:/run/php/api.sock;

}

location ~ \.php$ {

fastcgi_pass unix:/run/php/php8.2-fpm.sock;

}

Keeping complex regex locations at the end of the file and ordering them intentionally is a best practice for avoiding this confusion.

Misunderstanding the ^~ Modifier

Another frequent mistake involves the ^~ modifier. Some users assume that ^~ increases the priority of a location compared to regex matches even when the URI doesn’t start with the defined prefix. In reality, ^~ only applies if the request URI begins with the prefix. If it doesn’t, the rule is ignored, and the search continues as normal.

For instance:

location ^~ /media/ {

root /var/www/files;

}

location ~ \.jpg$ {

root /var/www/images;

}

A request to /images/logo.jpg will not use the /media/ block, even though ^~ is defined, because the path does not start with /media/.

The ^~ modifier is not a global priority mechanism; it is only a shortcut that tells Nginx to skip regex evaluation when a particular prefix is matched. If used incorrectly, it can lead to confusion or to certain regex rules being skipped unintentionally.

Directory vs. File Exact Matches

It’s easy to mix up directory-style and file-style locations, especially when both exist in the same configuration. For example:

location /downloads/ {

root /var/www/files;

}

location = /downloads {

return 301 /downloads/;

}

The second block matches /downloads exactly (without a trailing slash), while the first handles /downloads/ and everything beneath it. If the redirect in the second block is missing, users accessing /downloads will see a 404, even though /downloads/ is valid.

When defining directories, always include the trailing slash in the location pattern to make sure directory requests and their contents are handled correctly. If you want to handle both cases cleanly, you can use a short redirect:

location = /downloads {

return 301 /downloads/;

}

Unintended try_files Behavior

The try_files directive can cause unexpected routing if the order of arguments is incorrect or if the final fallback path points to a URI that triggers another internal redirect.

For example:

location / {

try_files $uri /index.html;

}

This configuration works for static content but can misbehave when used with dynamic applications. If /index.html doesn’t exist, Nginx returns a 404 instead of passing the request upstream. The safer pattern includes a fallback to a named location or proxy route:

location / {

try_files $uri /index.html @app;

}

location @app {

proxy_pass http://backend;

}

Using try_files with clear fallback logic ensures that missing files or rewritten URIs are always handled gracefully.

Wildcards in server_name

Misuse of wildcards in server_name definitions can cause requests to be routed to the wrong virtual server. A configuration like:

server_name *.example.com;

matches www.example.com, api.example.com, and any other subdomain. However, if another server block defines server_name example.com, requests for the bare domain (example.com) will not match the wildcard block and will instead fall back to the default server.

To handle both the root domain and its subdomains consistently, define both names explicitly:

server_name example.com *.example.com;

This avoids ambiguity and ensures predictable virtual host selection.

Ambiguous Server Blocks

Ambiguity often arises when multiple server blocks share the same listen directive but have similar server_name values. In such cases, Nginx will pick the one that most specifically matches the Host header, or the one marked as default_server if no explicit match exists.

Consider this configuration:

server {

listen 80 default_server;

server_name _;

return 444;

}

server {

listen 80;

server_name example.com;

root /var/www/example;

}

If the request uses a Host header not matching example.com, Nginx serves it from the default server and immediately closes the connection with a 444. While this can be intentional for security, it’s important to define the default server explicitly rather than assuming Nginx will pick one automatically.

Combining Regex and Prefix Without Care

Mixing regex and prefix locations can introduce subtle issues if their behaviors are not clearly understood. Prefixes are evaluated first, and only if the best prefix does not use ^~ will regex evaluation occur. For example:

location /api/ {

proxy_pass http://backend;

}

location ~ /api/v[0-9]+/ {

proxy_pass http://versioned_api;

}

In this setup, /api/v1/users matches both locations. Because /api/ is a prefix and doesn’t use ^~, Nginx proceeds to check regex locations. Since the regex matches, it is selected. If you want /api/ to handle all API paths regardless of regex rules, adding ^~ ensures that behavior:

location ^~ /api/ {

proxy_pass http://backend;

}

Best Practices

Understanding how Nginx selects server and location blocks is only the first step. Applying that knowledge effectively ensures configurations remain predictable, efficient, and easy to maintain. Over time, as your configuration grows, small inconsistencies or misplaced directives can lead to subtle routing issues. Following a set of consistent practices helps you avoid these problems while keeping your setup clean and scalable.

The following best practices are drawn from real-world deployments and community recommendations, as well as guidance from the official Nginx documentation.

Use Exact Matches Sparingly but Intentionally

Exact-match locations are the most specific form of URI handling. They are useful for small, fixed routes that should not overlap with others, such as health checks, static assets, or redirects. However, they should be used with clear intent and not as a replacement for prefix-based routing.

location = /robots.txt {

root /var/www/site;

}

location = /healthz {

return 200 'OK';

}

Overusing exact matches for ordinary paths can make configurations harder to maintain, especially when you need to modify routing later. Keep them for cases where the behavior should always be isolated and deterministic.

Prefer Prefix Matches for Directory-Level Routing

Prefix locations are fast, efficient, and ideal for serving static content or grouping related files under common directories. They avoid the computational overhead of regular expressions and are much easier to reason about visually.

For example:

location /static/ {

root /var/www/assets;

}

location /images/ {

root /var/www/images;

}

These blocks make it immediately clear which resources belong where. When working with complex directory hierarchies, prefix matches offer a balance between readability and performance.

Avoid Unnecessary Regular Expressions

Regular expression locations are powerful, but they introduce performance overhead and can make behavior harder to predict. They should only be used when prefix matching cannot achieve the same goal; for example, when matching file extensions or dynamic patterns.

A configuration that uses regex for every route is not only inefficient but also more error-prone. Instead of:

location ~* /static/.*\.(css|js|png|jpg)$ {

root /var/www/assets;

}

you can achieve the same result with a combination of prefixes and MIME-type handling:

location /static/ {

root /var/www/assets;

}

This approach is cleaner, faster, and easier to debug. Use regex sparingly, and when you do, place them near the bottom of the file to avoid unintended matches.

Place Regex Locations at the End of the Configuration

Because Nginx evaluates regex locations in the order they appear, always define them after all prefix and exact-match blocks. This ensures predictable evaluation and prevents general regexes from overriding specific path-based routes.

A good structure to follow is:

- Exact matches (

=) at the top. - Prefix matches (with and without

^~) next. - Regex matches (

~,~*) at the end.

This simple ordering pattern makes your configuration readable and consistent across projects.

Use try_files Carefully and Explicitly

The try_files directive is powerful but can be confusing if used without clear intent. It should always end with an explicit fallback (either a static file, a named location, or a defined error code) to avoid ambiguity.

location / {

try_files $uri $uri/ =404;

}

For applications that require dynamic routing or front-end fallbacks, use named locations or proxy blocks:

location / {

try_files $uri $uri/ @app;

}

location @app {

proxy_pass http://backend;

}

Avoid pointing try_files fallbacks directly to paths that may trigger new internal redirects unless that behavior is intentional.

Use return Instead of rewrite When Possible

The rewrite directive is often overused for simple redirects that can be handled more efficiently with return. The rewrite directive triggers URI parsing and, in some cases, internal redirects, which are unnecessary for static or permanent redirects.

Instead of:

rewrite ^/old-page$ /new-page permanent;

prefer:

return 301 /new-page;

The return directive is easier to read, faster to execute, and makes intent clear, especially for permanent or simple redirections.

Keep Server Block Ordering Predictable

When multiple server blocks listen on the same IP and port, the order in which they appear in the configuration can determine which one acts as the default. To make this explicit, always designate a default server:

server {

listen 80 default_server;

server_name _;

return 444;

}

This ensures that requests that do not match any defined server_name are handled in a controlled manner. Explicitly defining a fallback block also helps with debugging when unexpected routing occurs.

Structure Configurations for Readability

Complex configurations evolve over time. To keep them maintainable:

- Group related directives together.

- Use consistent indentation and spacing.

- Include comments to describe non-obvious behavior.

- Separate large configurations into included files (for example,

include conf.d/*.conf;).

Readable configuration files reduce mistakes and make it easier for others to understand or troubleshoot your setup.

Validate and Test Configurations Frequently

Even small syntax errors or misplaced directives can break Nginx behavior. Before reloading a configuration, always validate it:

- nginx -t

If the test passes, reload gracefully:

- nginx -s reload

For debugging routing behavior, use:

- curl -I -v http://example.com/path

and review which location block is serving the request. Enabling debug logging temporarily (error_log /var/log/nginx/error.log debug;) can also reveal how Nginx traverses locations and applies internal redirects.

Keep Configurations as Deterministic as Possible

A deterministic configuration behaves the same way for every request, without surprises. Avoid multiple overlapping patterns, use clear modifiers, and document any exceptions. When in doubt, test ambiguous routes explicitly. Predictability not only improves reliability but also simplifies long-term maintenance.

FAQs

1. Does Nginx process regex locations before prefix matches?

No. Nginx always evaluates prefix matches first, including both exact (=) and general prefix locations. Regex locations are only checked after Nginx finishes identifying the best prefix match.

The evaluation order is strict:

- Check for exact matches (

=). - Identify the longest prefix match.

- If that prefix uses

^~, stop and use it immediately. - Otherwise, evaluate regex (

~,~*) locations in configuration order.

This means regex locations never override exact or ^~ prefixes and are only considered after prefix evaluation. Regexes also require more processing, so they are deferred intentionally for performance reasons.

2. What does the ^~ modifier actually do?

The ^~ modifier tells Nginx to skip the regex phase if a matching prefix is found. It does not make a location higher priority in general, it only affects what happens once the URI begins with that prefix.

Example:

location ^~ /assets/ {

root /var/www/static;

}

location ~ \.(jpg|png)$ {

root /var/www/images;

}

A request to /assets/logo.png matches the /assets/ prefix, and because it uses ^~, Nginx stops there and does not test any regex rules (even though the .png pattern would also match).

You can think of ^~ as a directive that says, “If this prefix fits, don’t bother checking regex locations.”

It’s often used for static paths like /api/, /media/, or /css/ to prevent regex rules from interfering.

3. How do I debug which location Nginx selected?

To confirm which location handled a request, you can use several built-in Nginx tools. The most effective method is to enable debug logging temporarily:

error_log /var/log/nginx/error.log debug;

Then, make a request using curl -I -v http://example.com/path and review the error log. It will include lines like:

using configuration "/etc/nginx/nginx.conf"

rewrite or internal redirection to "/index.html"

using location: "/images/"

These messages show exactly which location was matched and whether any internal redirects occurred.

You can also log the variables $uri, $request_uri, and $request_filename in your access logs to see how Nginx transformed the request. For example:

- log_format debug '$remote_addr $request_uri => $uri => $request_filename';

Finally, you can run:

- nginx -T

to print the full configuration (including inherited blocks) and confirm the order and modifiers of all location definitions.

Together, these methods give you a complete picture of Nginx’s decision process.

4. Why is my exact match not triggering?

Exact matches only apply when the request URI exactly equals the specified string: no trailing slashes, query parameters, or case variations.

For example:

location = /index.html {

root /var/www/html;

}

This location matches /index.html but not /index.html/ or /index.html?v=1. If your requests include parameters, Nginx strips them before matching, but any additional path characters or case mismatches will still cause the match to fail.

In many cases, the issue is that the request ends with a slash or triggers an internal redirect (such as / being redirected to /index.html). In those cases, the rewritten URI might no longer match the = rule.

To confirm, enable debug logging and look for entries that show whether the URI was rewritten before matching. If your intent is to match multiple forms of the same path, a prefix or regex location may be more appropriate.

5. Does the order of location blocks matter?

It depends on the type of location:

- Prefix locations (

/path/,^~ /path/,/) are evaluated based on the longest match, not file order. The order in which they appear in the configuration file has no effect. - Regex locations (

~,~*), however, are order-dependent. They are tested sequentially in the order they are defined, and the first regex that matches wins.

For example:

location ~ \.php$ { ... }

location ~ /api/.*\.php$ { ... }

Here, the first regex captures all .php files, preventing the second from ever matching. Reversing the order gives the more specific pattern priority.

So while prefix locations are unaffected by configuration order, regex locations are sensitive to it, making proper placement essential for predictable results.

6. Why is the default_server block handling my request?

When multiple server blocks listen on the same IP and port, and none of their server_name values match the incoming Host header, Nginx sends the request to the server defined as default_server.

server {

listen 80 default_server;

server_name _;

return 444;

}

If no default is specified, Nginx uses the first server block it encounters as the implicit default. This can lead to confusion when requests are routed to an unexpected virtual host. Always define an explicit default_server to make behavior predictable.

7. Why is Nginx returning a 404 when the file exists?

A 404 may appear even if the file physically exists due to a mismatch between the URI and the filesystem path generated by the root or alias directive.

If you’re using alias, ensure the path correctly replaces the matched portion of the URI:

location /static/ {

alias /var/www/assets/;

}

With alias, the URI /static/logo.png resolves to /var/www/assets/logo.png. If you mistakenly use root instead:

location /static/ {

root /var/www/assets;

}

the resolved path becomes /var/www/assets/static/logo.png, which may not exist. Small path differences like this often explain unexpected 404s.

Conclusion

In this guide, we covered how Nginx selects the correct server and location blocks for each request, including how listen and server_name determine server selection and how locations are evaluated in order: exact match, longest prefix, optional ^~ shortcut, regex evaluation, and prefix fallback.

We also explained how directives like try_files, index, rewrite, and error_page can trigger internal redirects that restart the evaluation process, and how modifiers such as =, ^~, ~, and ~* influence matching behavior. Along the way, you explored common configuration pitfalls, best practices for predictable routing, and practical debugging techniques.

With these principles in mind, you can create Nginx configurations that are efficient, consistent, and easy to maintain, ensuring every request is handled exactly as intended.

For more Nginx tutorials, check out the following articles:

Thanks for learning with the DigitalOcean Community. Check out our offerings for compute, storage, networking, and managed databases.

About the author(s)

Former Senior Technical Writer at DigitalOcean, specializing in DevOps topics across multiple Linux distributions, including Ubuntu 18.04, 20.04, 22.04, as well as Debian 10 and 11.

With over 6 years of experience in tech publishing, Mani has edited and published more than 75 books covering a wide range of data science topics. Known for his strong attention to detail and technical knowledge, Mani specializes in creating clear, concise, and easy-to-understand content tailored for developers.

Still looking for an answer?

This textbox defaults to using Markdown to format your answer.

You can type !ref in this text area to quickly search our full set of tutorials, documentation & marketplace offerings and insert the link!

I had a question about an nginx problem last night. Found this article and boom, you explained nginx very well. Thank you!

(http://stackoverflow.com/questions/29935201/rate-limiter-not-working-for-index-page) My original question that I answered!

Justin,

Maybe you can help with this. I’ve posted on StackOverflow but I can’t seem to get any response.

I have a single index PHP application that uses a user defined keyword to route requests for that keyword to the admin section of the application.

In other words, it’s a dynamic url segment, a directory for it doesn’t exist.

In my case I’ve set the admin keyword to ‘manage’, so my url looks like:

http://example.com/manage/index.php?route=xxx/xxx&token=yyy

I’ve tried several location blocks but my thought is that this “should” work, but it doesn’t:

location /manage {

try_files $uri $uri/ @manage;

}

location @manage {

rewrite ^/(.+)$ /index.php?_route_=$1 last;

}

I’m an Nginx noob so any help would be greatly appreciated.

–Vince

After reading through,

I still can’t quite get it right. I might be missing something.

Say I have site1.com as my default server block. And site2.com in the next server block. Both are of different site and content.

Inputting www.site2.com would go to site2.com, as it should. However, if I were to put anything else, say testtube.site2.com or rollerskates.site2.com, I get directed to site1.com

The server_name line reads

server_name site2.com www.site2.com *.site2.com;

Why isn’t the wildcard domain working properly? Any ideas?

This post is awesome, thank you so far!

We’ve had a behavior of nginx with location within location i do not understand.

Our goal is to use basic HTTP Auth on a subdirectory named mon.

This was our config:

location /mon {

auth_basic "Monitoring";

auth_basic_user_file /etc/nginx/auth/mon-htpasswd;

}

location ~ [^/]\.php$ {

try_files $uri =404;

include fastcgi_params;

fastcgi_pass unix:/var/run/fpm.sock;

}

After reading this post i do actually understand why /mon/index.php was still accessible without authentication. Thank you!

Some research later we end up with this config:

location /mon {

auth_pam "Monitoring";

auth_pam_service_name "nginx.elwis_mon";

satisfy all;

location ~ [^/]\.php$ {

try_files $uri =404;

include fastcgi_params;

fastcgi_pass unix:/var/run/fpm.sock;

}

}

location ~ [^/]\.php$ {

try_files $uri =404;

include fastcgi_params;

fastcgi_pass unix:/var/run/fpm.sock;

}

So, this actually works… but why? As you mentioned, there is the “only one location block” rule, this shouldn’t work at all.

I don’t understand the section that discusses the index directive. How does a request to the URI /exact end up being processed by a block that matches location “/” if the inherited index is set to index.html? Could you walk us through how that works?

Great info in here Justin, thanks for sharing. Much more approachable than the nginx official docs ( which are sorely lacking for such a great product).

Hi,

nice article but I cannot make something:

I want to have all http to https and only some paths to http with different ports:

server {

listen 80;

server_name _;

return 301 https://$host$request_uri;

location /bamboo {

rewrite ^/bamboo(.*)$ http://mydomainname:8085/$1 last;

}

location /api {

rewrite ^/api(.*)$ http://mydomainname:8080/$1 last;

}

return 403;

}

the above does not work,

also this does not work:

# Redirect paths

#

server {

listen 443;

server_name _;

location /bamboo {

rewrite ^/bamboo(.*)$ http://mydomainname:8085/$1 last;

}

location /api {

rewrite ^/api(.*)$ http://mydomainname:8080/$1 last;

}

return 403;

}

# Redirect http -> https

#

server {

listen 80;

server_name _;

return 301 https://$host$request_uri;

return 403;

}

I’m having some issue here with a request to an API. Everything works with proxying with following nginx location:

location / {

proxy_set_header X-Real-IP $remote_addr;

proxy_set_header Host $host;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-Proto $scheme;

proxy_set_header X-NginX-Proxy true;

proxy_set_header Upgrade $http_upgrade;

proxy_set_header Connection "";

add_header Cache-Control "public";

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-Host $host;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-Server $host;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-For $proxy_add_x_forwarded_for;

proxy_http_version 1.1;

proxy_pass http://127.0.0.1:3000;

}

With the above I can get to URLs like https://domain.com/main/found/users

However, as soon as I try to use the API I get a 404 back. The URL to an API call looks like:

https://domain.com/api/v1/users/find

In the nginx error log I then see an entry like:

[error] 1137#0: *3552 open() "/usr/share/nginx/html/api/v1/user/find" failed (2: No such file or directory)

Obviously files are not stored there as they should be served by the proxy.

Totally confused here, so an advice greatly appreciated. Thank you.

Wow, absolutely excellent writeup Justin! Your writing style is so clear, and your inclusion of examples for each thing you’re explaining is incredibly helpful. Thank you!

This comment has been deleted

- Table of contents

- Introduction

- Why Server and Location Selection Matters

- Understanding Nginx Configuration Blocks

- How Nginx Selects the Server Block

- Understanding Location Block Types

- How Nginx Selects the Location Block

- Common Configuration Pitfalls

- Best Practices

- FAQs

- Conclusion

Deploy on DigitalOcean

Click below to sign up for DigitalOcean's virtual machines, Databases, and AIML products.

Become a contributor for community

Get paid to write technical tutorials and select a tech-focused charity to receive a matching donation.

DigitalOcean Documentation

Full documentation for every DigitalOcean product.

Resources for startups and SMBs

The Wave has everything you need to know about building a business, from raising funding to marketing your product.

Get our newsletter

Stay up to date by signing up for DigitalOcean’s Infrastructure as a Newsletter.

New accounts only. By submitting your email you agree to our Privacy Policy

The developer cloud

Scale up as you grow — whether you're running one virtual machine or ten thousand.

Get started for free

Sign up and get $200 in credit for your first 60 days with DigitalOcean.*

*This promotional offer applies to new accounts only.